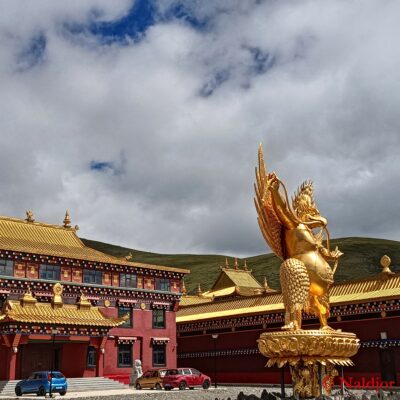

The Giant Golden Khyungchen at Gegong Gön’s Shedra is more than an impressive sculpture. It is a highly charged cultural object, a guardian presence shaped by centuries of Tibetan religious imagination. When visitors first walk into the courtyard and see the enormous wings spread wide, they often pause. Something in its posture feels ancient, almost older than Buddhism itself. And in a sense, that is true. The Khyung (ཁྱུང་) reaches back into pre-Buddhist Himalayan mythology and later becomes fully absorbed into Nyingma ritual cosmology. The Shedra places this figure at its entrance because it communicates a single message: knowledge needs protection, and learning requires courage.

The Khyung, or Tibetan Garuda, is a mythical bird with roots in both Bön and early Himalayan folklore. It is fierce, fast, and uncompromising.

It is traditionally invoked to neutralize naga-related illnesses, curse-like obstacles, or stagnant energies believed to block learning and clarity. This is why Khyungchen appears not only in warrior dances but also in philosophical universities. Its energy is not simply martial. It is epistemic. It protects knowledge.

The suffix chen (ཆེན་) means “great,” but in ritual contexts it denotes escalation. A Khyungchen is not just a large Garuda. It is a wrathful magnification of its qualities — sharper vision, broader wingspan, and a fearless stance used to cut through ignorance. A key verse from a Nyingma terma states:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་རྣམ་གྲོལ་ལམ་གྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ།

“The Great Khyung is the manifestation of the path of liberation.”

This connection between the bird and liberation explains why it stands at the threshold of a Shedra. Students who walk past it daily do so under the wings of a being symbolizing intellectual freedom.

Long before Buddhism entered Tibet, the Khyung already occupied a central place in the mythic geography of the Himalayas. Archaeological motifs in rock carvings from Mustang and Zhangzhung show bird-headed figures with outstretched wings. These early carvings don’t label the creature, but local Bön traditions describe something very similar. One Bön scripture, the Gzer mig, includes the line:

ཁྱུང་གི་རྒྱལ་བ་འོད་དཔག་མེད།

“The king of Khyung shines with immeasurable radiance.”

This indicates that the Khyung was already understood as a force of protection and brilliance. Not a demon. Not a monster. A sovereign being tied to sky-power and clarity.

During the Tibetan Empire (7th–9th centuries), the Khyung becomes a political symbol. Some imperial seals feature winged birds believed to be early Khyung prototypes. The Old Tibetan Chronicle even contains a heroic line comparing the emperor’s strength to:

ཁྱུང་དགའ་རྒྱལ་བའི་སྟོབས།

“the might of a victorious Khyung.”

This period marks the first fusion of myth and authority. The bird shifts from mythic creature to emblem of sovereignty and protection of law — ideas that later integrate naturally into Buddhist protector roles.

When Buddhism spread through Tibet, Nyingma masters absorbed local deities instead of replacing them. The Khyung fit seamlessly into tantric cosmology. Its wrathful energy matched the role of enlightened protectors who destroy ignorance. The Guhyagarbha Tantra mentions bird-like deities rising from wisdom fire:

ནོར་བུའི་མེ་ལས་ཁྱུང་མཆོད་འཕྲོ།

“From the jewel-fire, the Khyung-offering arises.”

Although not naming the Khyung explicitly, later Nyingma commentators saw the connection and incorporated it into rituals, especially those related to clearing obstacles, illness, and spiritual stagnation.

Eastern Tibet (Kham) holds the strongest Khyung traditions. Local tertöns revealed numerous terma identifying the Khyung as guardian of mountains, valleys, and teaching centers. One widely cited terma fragment says:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་གནས་སྐྱོང་སྲིད་པ་རྒྱལ།

“The Great Khyung guards the sacred ground and conquers the worldly forces.”

Because Gegong Gön is located in Kham, its Shedra inherits this regional emphasis. Almost every major Shedra in Kham features a Khyung at its gate, rooftop, or assembly hall. The idea is simple but profound: education is vulnerable, and knowledge requires guardianship.

Gegong Gön, located in eastern Tibet, is known for its strong Nyingma heritage and a pedagogical philosophy that blends scholarship with ritual protection. A giant Khyungchen stands at its Shedra because the tradition holds that philosophical study invites subtle forms of disturbance. Some are intellectual, some emotional, and some energetic. The Khyungchen is believed to stabilize the field of learning.

The logic is expressed in a local saying recorded in oral histories: “Where Dharma is studied, Khyung spreads its wings.”

It implies that learning itself generates energy that needs guarding. Shedra training is demanding, and monks often describe the Khyung as a reminder that clarity requires resilience.

If we compress everything the Khyungchen symbolizes, we find three recurring messages:

These are not exotic ideas. They are deeply practical. They explain why the Khyung is not limited to mythic stories or warrior dances. It survives because the inner obstacles it addresses also survive.

In many Nyingma monasteries, the Khyungchen is not simply an ornament. It participates in the ritual ecosystem. Monks walk past it before daily recitations. Khenpos teach near its shadow. Novices catch glimpses of the wings during discipline rounds. Over time, the figure becomes part of the psychological landscape. A protective presence. A reminder of vigilance. This sense of ritual companionship is typical of Tibetan culture, where symbols are not abstract—they are living presences woven into daily rhythm.

By the 17th century, Tibetan art lineages like Menri and Khyenri standardized the Khyung’s appearance. The giant wings, sharp beak, upright posture, and flaming aura all became consistent features. This visual grammar allowed monasteries to place the Khyung in predictable architectural spots: gateways, rooftops, teaching halls, and ritual spaces where clarity and protection are needed. The symbolism of Khyungchen is not mysterious. It is built around three primary qualities: sharpness, height, and clarity. Tibetan sources often describe it with lines like:

ཁྱུང་གི་སྤྲུལ་པ་མི་རབ་ཏུ་རྣམ་པ།

“The manifestation of the Khyung is supremely clear.”

For Shedra students, these qualities translate into intellectual virtues. Sharpness becomes analytical precision. Height becomes broad perspective. Clarity becomes the ability to see through confusion. This is why the bird stands tall at the school’s entrance: the message is direct—study is an act of seeing from above.

The size of the Khyungchen is deliberate. A small statue would signal respect. A giant one signals presence. Tibetan scholastic culture frequently uses physical scale to teach psychological lessons. Something large tilts the emotional field. It interrupts habitual patterns. The imposing wingspan reminds students that the world is wider than their personal concerns.

Tibetan artists continue to draw and sculpt the Khyungchen with remarkable consistency. The wings always flare upward, the beak points forward, and the flames curl around the body. These visual conventions are not arbitrary. One artist from Derge explained that the curling flames represent the motion of insight: fast, irregular, and unstoppable.

In artistic terms, that means the image reminds viewers to stay awake in their ethical and intellectual lives. Contemporary thangka painters sometimes exaggerate the wingspan to emphasize this expansive alertness.

The Khyung, or Tibetan Garuda, is a mythical bird with roots in both Bön and early Himalayan folklore. It is fierce, fast, and uncompromising. Tibetan texts describe it with lines such as:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་མཐའ་ཡས་བརྒྱན་ལས་འགྲོ།

“The great Khyung moves beyond all limits of obstruction.”

It is traditionally invoked to neutralize naga-related illnesses, curse-like obstacles, or stagnant energies believed to block learning and clarity. This is why Khyungchen appears not only in warrior dances but also in philosophical universities. Its energy is not simply martial. It is epistemic. It protects knowledge.

The suffix chen (ཆེན་) means “great,” but in ritual contexts it denotes escalation. A Khyungchen is not just a large Garuda. It is a wrathful magnification of its qualities — sharper vision, broader wingspan, and a fearless stance used to cut through ignorance. A key verse from a Nyingma terma states:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་རྣམ་གྲོལ་ལམ་གྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ།

“The Great Khyung is the manifestation of the path of liberation.”

This connection between the bird and liberation explains why it stands at the threshold of a Shedra. Students who walk past it daily do so under the wings of a being symbolizing intellectual freedom.

Protection in Tibetan Buddhism does not mean shielding one from challenges. It means transforming challenges. The Khyungchen stands at the Shedra because intellectual study brings its own obstacles: pride, fatigue, competitiveness, doubt, and sometimes emotional heaviness. The bird’s fierce posture speaks directly to those internal patterns. A verse in a ritual text states:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་གནོད་སྦྱིན་མེ་ལས་སྲུང་།

“The Great Khyung guards through the fire that dispels harm.”

In psychological terms, the Khyung’s fire symbolizes the capacity to metabolize emotional confusion rather than suppress it. Students often report that simply seeing the statue during stressful study seasons brings a sense of groundedness.

Outside the monastery, the Khyung carries a different meaning. Villagers often see it as a protector against naga illnesses, unpredictable weather, or emotional heaviness in the home. One elder from Kham explained it plainly: “The Khyung keeps the wind clean.”

Though metaphorical, the idea aligns with Tibetan medical and energetic systems that associate clarity with balanced winds (rlung). When a giant Khyung is placed near a Shedra, villagers interpret it as protection not just for monks but for the whole valley.

(Source Naldjor)

Nyingma philosophy, especially Dzogchen, emphasizes awareness that cuts through conceptual complexity. The Khyung is a perfect metaphor. It flies above details but sees everything sharply. The Khyungchen embodies this attitude: direct, free, unbound by intellectual clutter. This does not mean anti-intellectual. It means study must eventually open into spacious understanding. Shedra education presents structure; the Khyung reminds students that the purpose of structure is freedom.

In today’s Nyingma monasteries, the Khyungchen remains an active ritual figure. It is invoked during obstacle-clearing ceremonies, especially in periods of communal tension, illness, or environmental unpredictability. The rationale is simple: the Khyung represents unblocked motion. It slices through stagnation. A modern ritual text used at Gegong Gön includes the line:

ཁྱུང་ཆེན་མེ་འཁོར་གྱིས་སྒྲོལ།

“The Great Khyung liberates through its ring of flame.”

This verse is chanted not as myth, but as a psychological and energetic reminder that clarity can be fierce and transformative. Ritual specialists often remark that the Khyung is “called” when the community needs to reset its emotional climate.

Gegong Gön, located in eastern Tibet, is known for its strong Nyingma heritage and a pedagogical philosophy that blends scholarship with ritual protection. A giant Khyungchen stands at its Shedra because the tradition holds that philosophical study invites subtle forms of disturbance. Some are intellectual, some emotional, and some energetic. The Khyungchen is believed to stabilize the field of learning. The logic is expressed in a local saying recorded in oral histories: “Where Dharma is studied, Khyung spreads its wings.”

It implies that learning itself generates energy that needs guarding. Shedra training is demanding, and monks often describe the Khyung as a reminder that clarity requires resilience.

In monastic education, the Khyungchen is used as a metaphor for the qualities students must cultivate. Khenpos often draw on the bird’s characteristics when teaching logic, philosophy, or Madhyamaka debate. They describe three “Khyung skills”:

These are not abstract ideals. They shape how a monk learns to think. Some Shedra classrooms even place a small Khyung carving on the teacher’s table as a teaching reminder. The message is not mystical. It is pedagogical.

Some modern Nyingma teachers incorporate the Khyungchen into meditation instruction. They use its imagery to teach fearlessness or to help practitioners confront internal turbulence. Practitioners visualize the wings spreading across the sky, dissolving obstacles into space. This is not elaborate tantric practice. It is a simple stabilization method meant to restore momentum when a meditator feels stuck.

The Giant Golden Khyungchen at Gegong Gön’s Shedra is more than a relic of myth. It continues to resonate because its symbolism addresses something fundamentally human. We all struggle with confusion, stagnation, doubt, and the weight of our own minds. The Khyungchen stands for the possibility of cutting through that heaviness. It does not promise perfection. It promises movement. That is why students, villagers, monks, artists, and teachers continue to feel drawn to its image.

What keeps the Khyungchen alive is not tradition alone. It is usefulness. The bird speaks to human psychology. It speaks to students, teachers, villagers, scholars, and modern practitioners. In Gegong Gön’s Shedra, it stands at the threshold like a quiet guardian. The Khyungchen can live as a reminder that wisdom is both sharp and compassionate, both fierce and gentle. A final fragment from a ritual hymn captures this beautifully:

It is an image of freedom. And that, ultimately, is the purpose of Shedra education.

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY