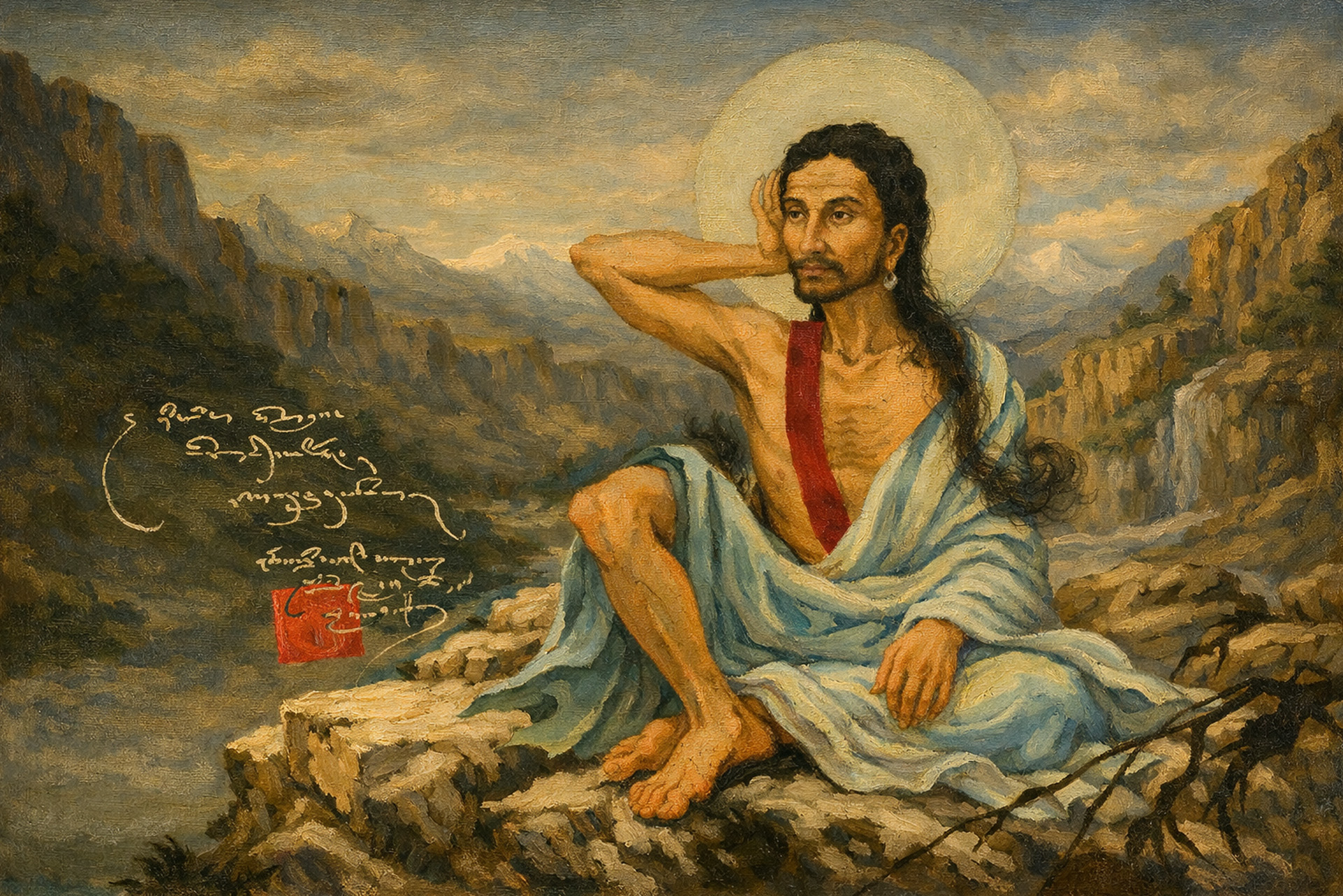

Thöpaga (ཐོས་པ་དགའ་) (1052-1135) – Spiritual name / historical name: Milarepa (མི་ལ་རས་པ་)

Some spiritual stories inspire because they are beautiful.

Milarepa’s story inspires because it is honest.

His life does not begin in virtue or serenity. It begins in grief, injustice, and rage. As a child, Milarepa lost his father and, with him, the security of his world. Betrayed by relatives, stripped of dignity, and consumed by humiliation, he grew up carrying a wound that never healed quietly.

In his anger, he chose the wrong path. He learned destructive magic. He caused real harm. Lives were lost because of him.

Buddhism does not erase this part of Milarepa’s story. It does not soften it. And that is precisely why his life matters.

Milarepa teaches us that awakening does not belong only to the innocent.

What transformed him was not a sudden miracle, but the slow, unbearable weight of remorse. He did not seek liberation because it sounded noble. He sought it because he could no longer live with what he had become.

When Milarepa finally found his teacher, Marpa, he was not met with comfort. He was met with labor, silence, rejection, and exhaustion. Tower after tower was built and destroyed. Hope rose and collapsed. Pride was stripped away layer by layer.

This was not cruelty. It was precision.

Marpa understood that Milarepa’s suffering could not be healed by words alone. The same intensity that once fueled destruction had to be turned inward until it became clarity instead of violence.

Later, alone in mountain caves, Milarepa faced hunger, cold, fear, and hallucination. Demons appeared, but he did not fight them. He invited them in. When fear was met without resistance, it dissolved.

From this solitude came his songs simple, direct, deeply human. They speak not of achievement, but of relief. Not of mastery, but of freedom from struggle.

Milarepa’s life reassures us of something quietly radical:

no one is beyond transformation.

His path was not gentle, but its fruit was compassion without pretense. He did not become holy by escaping suffering. He became free by understanding it completely.

Milarepa does not ask us to admire him.

He asks us to believe that our own darkness is workable.

After receiving instruction, Milarepa withdrew into near-total solitude. He lived in caves, clothed in rags, surviving on nettles. His body weakened; his mind sharpened.

Milarepa’s realization unfolded not through scholarly debate but through direct confrontation with fear, hunger, and isolation. Demons appeared not as external beings, but as manifestations of unresolved mind. Instead of fighting them, he fed them. In doing so, he dissolved their power.

This radical intimacy with suffering gave rise to Milarepa’s spontaneous songs (dohas), expressions of realization unfiltered by doctrine. His poetry remains one of the most human voices in Buddhist literature—raw, luminous, unsentimental.

Milarepa became the archetype of the Tibetan yogi: renunciant, itinerant, uncompromising. He rejected institutional authority, wealth, and comfort not out of asceticism for its own sake, but because distraction weakened clarity.

He taught through presence rather than system. His disciples included farmers, hunters, monks, and wanderers. His successor, Gampopa, bridged Milarepa’s yogic lineage with monastic structure, giving rise to the Kagyu school.

Through this lineage, Milarepa’s life shaped Tibetan Buddhism for centuries not as myth, but as method.

Milarepa’s story is not only about his own transformation but also about the power of a spiritual master to guide a disciple toward enlightenment. It highlights the importance of patience, humility, and perseverance on the spiritual path. Milarepa went on to teach many others, leaving behind a rich legacy of teachings and songs that continue to inspire practitioners today.

One of Milarepa’s famous songs expresses his profound realization of the impermanence of life and the importance of devotion to the Dharma:

Milarepa endures because he addresses a universal fear: “I have gone too far. I am beyond repair.” His life answers decisively no.

He demonstrates that:

Milarepa’s legacy is not heroic perfection, but honest transformation. He reminds us that wisdom is not the absence of suffering, but intimacy with it—so complete that it loses its grip.

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY