Six-Arm Mahākāla is one of the most widely invoked Dharma Protectors in Tibetan Buddhism, especially within the Kagyu and Sakya traditions. Although Mahākāla appears in Indian tantric literature as a fierce wisdom deity, his Tibetan forms evolved through multiple ritual lineages, artistic systems, and scholastic interpretations. This study examines the Six-Arm manifestation through historical sources, Tibetan ritual manuals, doctrinal commentaries, and Himalayan art. It also analyzes his relationship to Avalokiteśvara, his symbolic attributes, his role in protecting monastic institutions, and the ritual environments in which practitioners engage him. By tracing both textual and oral traditions, this article clarifies how Six-Arm Mahākāla functions not only as a wrathful guardian but also as an embodiment of fierce compassion meant to remove obstacles on the Buddhist path.

The earliest traces of Mahākāla appear in Indian tantric materials where he functions as a fierce guardian linked to time, decay, and the dissolution of obstacles. Several early sources portray him not as a demon but as a wrathful face of awakened wisdom. His role is to cut through hindrances that prevent meditation and to neutralize forces that disturb ritual sanctity. These materials do not yet describe a six-armed form. They present a deity whose intensity is meant to protect concentration and sustain the integrity of practice. What later becomes Tibetan protector worship grows from this set of ritual concerns.

In India, protectors appear in ritual settings as guardians of sacred boundaries, but they are not always personalized deities. Over time, figures like Mahākāla became individualized protectors who respond to invocation. Tibetan ritual culture embraced this shift and expanded it dramatically. Instead of remaining a minor guardian, Mahākāla evolved into a central Dharmapāla whose presence frames daily monastic life, festival cycles, and the schedules of meditation retreats. What began as a general ritual guardian became, in Tibet, a protector with personality, history, and relational presence.

Mahākāla enters Tibet through translation efforts and through ritual transmissions that accompany tantric practice. His earliest Tibetan appearances show a figure already important enough to be included in larger cycles of protection, purification, and boundary rites. Once integrated into Tibetan ritual life, Mahākāla gained new layers of meaning that reflect the concerns of Himalayan communities. He became a guardian of monasteries, a protector against social turmoil, and a deity who watches over those traveling through mountain passes. This broader protective role reflects how Tibetan culture tends to merge spiritual protection with the realities of terrain and communal life.

A pivotal development in the history of Mahākāla is his association with Avalokiteśvara. Indian tantric traditions occasionally describe wrathful forms of compassionate bodhisattvas, and Tibetan sources identify Mahākāla as a fierce manifestation of Avalokiteśvara’s compassion. This link supplies the ethical and doctrinal justification for his wrath. His violence is understood as a sharp method of mercy, a force that clears obstacles not out of anger but from deep care for practitioners. Tibetan masters often emphasize that without compassion, Mahākāla’s wrath would lose its legitimacy.

The six-armed configuration develops later. Early Indian material describes Mahākāla with varying attributes, sometimes two arms, sometimes four. The shift to six arms likely occurred when Tibetan ritual specialists sought a form that could embody the full range of compassionate action represented by the six perfections. Later Tibetan commentaries make this symbolic logic explicit, but the origin itself seems to grow from ritual creativity rather than a single authoritative source. The six arms express capability, not multiplication of physical force. They allow one deity to hold multiple methods needed to remove obstacles both subtle and gross.

The earliest Tibetan references to Mahākāla in surviving materials are sparse, and many early ritual texts likely disappeared. This gap forces scholars to rely on later materials while acknowledging that part of the story remains unknown. Such uncertainty is common in Tibetan protector studies. Where documentation is thin, ritual memory and artistic representation become crucial. They are sometimes more stable than textual records, and they help preserve a sense of continuity that written sources alone cannot provide.

In Tibetan Buddhism, wrath is never taken at face value. Six-Arm Mahākāla embodies a form of compassion that moves quickly and decisively. Tantric philosophy often describes such wrath as a method for cutting through habits that do not yield to gentle encouragement. This is why Tibetan commentators repeatedly insist that Mahākāla’s ferocity is an extension of Avalokiteśvara’s compassion rather than a departure from it. Without this foundation, his wrath would be spiritually meaningless. Although ritual texts speak confidently about this linkage, teachers sometimes acknowledge that the emotional tone of Mahākāla’s imagery can be difficult for beginners, and they encourage students to let meaning unfold gradually through practice.

Wrathful deities raise immediate philosophical questions. How can wrath coexist with non-harming? Tibetan commentaries respond by redefining wrath. It is directed at delusion, not beings. It interrupts harmful patterns when gentler methods fail. Six-Arm Mahākāla shows this principle vividly.

The philosophical challenge of Mahākāla is to integrate wrath and stillness without contradiction. Tibetan scholars often treat this as a test of one’s understanding of non-duality. If wrath and peace appear mutually exclusive, the practitioner has not yet grasped their shared nature. In advanced teachings, Mahākāla becomes a symbol for the inseparability of clarity and energy. His image reminds practitioners that spiritual life demands both.

A traditional line says:

Tibetan citation:

ཞི་དང་དྲག་པ་མ་ཟད་ལ་མཉམ་པར་འབྱུང་།

Wylie: zhi dang drag pa ma zad la mnyam par ’byung

English: “Peace and wrath arise together without remainder.”

A frequent point of discussion in Tibetan scholastic circles is how wrathful deities avoid contradiction with Buddhist non harming principles. Six-Arm Mahākāla becomes a central example. His gestures and weapons can look violent, yet ritual commentaries stress that these actions are directed at ignorance, not beings themselves. Monastic teachers often clarify that the imagery is symbolic even when the rituals feel intense. Students are reminded that the only permissible target of Mahākāla’s wrath is that which obstructs awakening. This distinction, although simple, becomes a cornerstone for understanding why protector practice can exist within a tradition grounded in compassion.

Tibetan traditions rarely allow an influential deity to stand without doctrinal grounding. A protector must be aligned with Buddhist ethics, or else the practice risks sliding toward superstition. For Six-Arm Mahākāla, the doctrinal anchor lies in the six perfections. Each arm corresponds to one perfection, and each perfection expresses a mode of compassionate activity. This mapping is not always explained in early sources, but later Tibetan writers found it necessary to clarify it. Their commentaries show a desire to link ritual power to the broader Buddhist path. Even when the origins of a form are unclear, Tibetan scholars work backwards to establish coherence.

The six arms of Mahākāla correspond to the six perfections not only symbolically but functionally.

In another hand, each arm holds an implement corresponding to one perfection. The mapping is not mechanically fixed across all lineages, yet the underlying logic remains stable. The perfections anchor the deity’s wrath in compassion.

Typical associations include:

Tibetan term for the six perfections: ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕར་ཕྱིན་པ་དྲུག

Six-Arm Mahākāla belongs to the category of wisdom protectors. This functional reading helps connect Mahākāla worship to the everyday challenges of practice. In this sense, the deity serves less as an external guardian and more as a mirror for inner work.

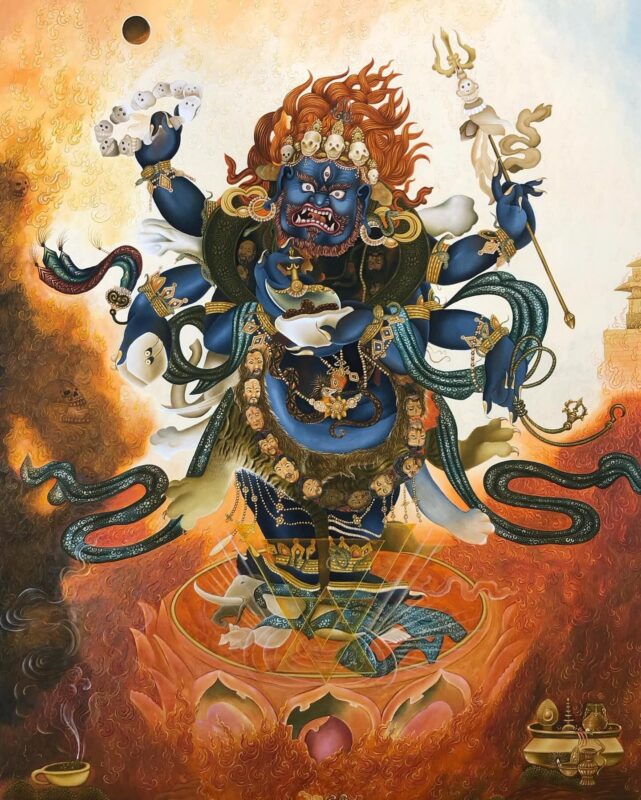

In Tibetan art, Six-Arm Mahākāla appears with a compact and powerful body, dark in color, surrounded by flames. The darkness is not meant to signal evil. Painters often explain it as the color of a night that absorbs everything without being harmed. The flaming aura suggests the heat of awareness that burns through confusion. The eyes are wide and somewhat uneven, a detail that artists say expresses both vigilance and a slight impatience with obstacles. None of these elements aim to frighten the practitioner. They are visual reminders that compassion sometimes needs force to act swiftly.

The Stance and the Trampled Figures: Mahākāla stands with one leg bent and one leg straight, a pose sometimes called the “action stance.” It expresses readiness and constant movement. Under his feet lie figures representing inner obstacles. Tibetan teachers often emphasize that these are not actual beings but personifications of confusion. The act of stepping on them is a visual teaching. Practitioners are meant to imitate this gesture internally, pressing down the emotional and conceptual patterns that block insight. The stance, therefore, is both a cosmological claim and a meditative instruction.

Tibetan teachers frequently reflect on the meaning of Mahākāla’s trampling posture. They argue that the crushed figures symbolize inner fears, not external enemies. By stepping on these forms, the deity models a direct approach to emotional obstacles. Practitioners are encouraged to internalize this gesture, pressing down confusion rather than negotiating with it. This interpretation reveals a psychological dimension: protector practice is not only about external safety but about stabilizing the mind when fear rises.

The Three Eyes and Panoramic Awareness: Mahākāla’s three eyes symbolize perception across past, present, and future. However, Tibetan explanations rarely treat this literally. The three eyes point to a more practical teaching: the awareness that can watch body, mind, and environment at once. Some commentaries describe this as “broad awareness seated on firm ground.”

Tibetan citation:

མིག་གསུམ་ནི་ཤེས་རབ་སྤྱི་མངོན།

Wylie: mig gsum ni shes rab spyi mngon

English: “The three eyes are the clear manifestation of general wisdom.”

The eyes are therefore not decorations. They mirror the panoramic attention that advanced meditation demands.

The Six Arms: General Framework: The six arms form the structural center of this iconography. Each arm holds a specific implement. The implements differ across lineages, and artists sometimes adjust them to match local ritual needs. Despite this variety, the six arms consistently represent the six perfections. The logic is simple. Compassion expresses itself in many ways, so the body of the deity must be able to enact many gestures at once. These arms are not additions for spectacle. They are functional symbols of skillful means.

The Chopper (kartika): In the upper right hand, Mahākāla often holds a crescent-shaped chopper. Tibetan teachers say its curved blade is designed to sever confusion at the root rather than at the branches. It has the reputation of being the most decisive of the implements.

The Skull Cup (kapāla): Another hand holds a skull cup filled with symbolic essence. Commentaries explain that this cup collects the “nutrients” of transformed emotions. It is a teaching on turning harmful patterns into fuel for the path.

The Rosary or String of Jewels: The rosary represents continuous practice. Artists often depict it in motion, suggesting steady effort.

The Trident or Staff: When present, the trident signifies the unity of body, speech, and mind, held firmly in awakened awareness.

The Noose: The noose functions as a metaphor for catching runaway thoughts. It is not a weapon but a reminder to reel the mind back in when it wanders.

The Drum (damaru) or Club: This implement varies the most. When it is a drum, it calls beings to awareness. When a club, it symbolizes strength used with wisdom.

The flames around him operate differently. They represent the heat of wisdom burning through conceptual rigidity. The contrast between absorbing darkness and blazing fire gives Mahākāla a symbolic depth that practitioners often describe as both grounding and energizing.

Color, Texture, and Painterly Conventions: Tibetan painters consistently use deep blue-black for Mahākāla’s skin. They describe it as a tone that absorbs negativity without letting it scatter. The flames around his body are usually layered in three colors to mark increasing heat, a detail maintained across regions. The ground beneath him sometimes includes small offerings or fragments of ritual space. These visual elements help align the deity with the ritual room, creating a space where the practitioner feels accompanied rather than overwhelmed.

Mahākāla is one deity, but Tibetan Buddhism is a tapestry of lineages, each with its own ritual style and philosophical emphasis. As a result, the Six-Arm Mahākāla appears in different ways depending on where he is practiced. These variations do not suggest contradiction. Instead, they show how Tibetan traditions adapt a shared figure to serve the needs of their communities. Teachers often remind students that protector deities respond to relationship more than to uniformity. This means the specific form one practices can meaningfully shape one’s experience of Mahākāla.

In the Kagyu school, Six-Arm Mahākāla is the primary protector. Ritual manuals often describe him not as a distant cosmic force but as a close guardian who moves with practitioners through their daily challenges. The Kagyu view highlights Mahākāla’s speed and responsiveness. Teachers note that these traits mirror the dynamic approach of Mahāmudrā, where the emphasis is on direct experience rather than elaborate conceptual analysis. Kagyu rituals tend to be vigorous but not overly ornate. They encourage practitioners to treat Mahākāla as a companion who clears obstacles on the spot.

In Sakya, Mahākāla is understood within the wider framework of the Lamdré teachings. This system organizes practice into a structured path, so Mahākāla becomes one piece of a carefully arranged mandala. His six arms are read as six ways to stabilize the practitioner as they move through graduated stages of view and meditation. Sakya scholars sometimes debate whether Mahākāla should be treated more as a ritual employee or as a wisdom emanation fully equal to other tantric deities. The tradition ultimately treats him as both. He protects, but he also educates the mind through his appearance and gestures.

In the Nyingma school, Mahākāla appears through several terma cycles. These revealed texts preserve distinct ritual styles. Some portray Mahākāla as more solitary and meditative, focusing on internal protection. Others emphasize communal rituals that ward off social misfortune or environmental disturbances. The six-arm form is present but not always central. Nyingma teachers often describe wrathful protectors as extensions of the guru principle, meaning that their power depends heavily on devotion and transmission. This approach reflects Nyingma’s broader philosophy, where personal connection to the lineage holds more weight than stylistic uniformity.

In the Gelug school, Four-Arm Mahākāla is often the primary protector, yet Six-Arm Mahākāla remains respected. Gelug monasteries generally maintain a more cautious approach, ensuring that protector practice stays aligned with monastic discipline. Teachers sometimes remind students that wrathful deities should not be seen as shortcuts to spiritual progress. They pair protector rituals with rigorous study and ethical training. Some Gelug commentators note that the six-arm form offers a valuable reminder that energy without discipline can become scattered. For Gelug practitioners, Mahākāla’s power is strongest when paired with a stable daily schedule.

Despite the differences, several points remain constant across the Tibetan schools. Mahākāla is universally regarded as a guardian of Dharma, not a worldly spirit. His wrath is grounded in compassion. His rituals aim to protect clarity so that meditation and study can mature. Each tradition accepts that Mahākāla is responsive, that sincere practice matters more than technical mastery, and that protector worship works best when tied to a disciplined ethical life. These shared principles create a common foundation that allows the diversity of Mahākāla forms to coexist without conflict.

In many Tibetan monasteries, especially within Kagyu and Sakya lineages, Six-Arm Mahākāla frames the rhythm of the day. The protector is invoked at dawn to clear obstructive conditions before study and meditation begin. The ritual does not aim at spectacle. Monks recite quietly, sometimes with the sense that the deity is more like a steady presence than a dramatic force. Teachers often tell students that daily Mahākāla practice is less about asking for help and more about preparing the mind for work. The simplicity of this framing lets the ritual blend smoothly with monastic life without dominating it.

Evenings often include a shorter Mahākāla section. This is sometimes called the “closing of the day,” where practitioners symbolically return whatever disturbances arose during study or community activity to the protection of the deity. Some lineages describe this as an ethical reflection. Others read it as a clearing of emotional residue. The ritual is brief, usually less than ten minutes, yet monks often claim it helps reset the mind for sleep. This suggests that the protector practice is not only a spiritual safeguard but also a form of practical mental hygiene.

In many monasteries, Mahākāla appears in cham dance, a ritual performance where monks enact deities through movement. The Six-Arm Mahākāla cham is physically demanding. The dancer must hold the intensity of the deity while staying aware of rhythm and space. Teachers say that cham is not theater but meditation in motion. Through dance, the community sees Mahākāla’s presence embodied. Many villagers describe cham as the moment when they feel most directly protected. Scholars sometimes debate whether cham is more artistic or more ritualistic. Practitioners tend to ignore the distinction, experiencing the dance as its own kind of blessing.

Although protector worship is strongest in monasteries, many Himalayan households maintain a small Mahākāla shrine. The images are simpler and the rituals shorter. Families recite brief praises to ask for stability in work, travel, and health. Lay practitioners understand Mahākāla less through scholastic theory and more through generational stories about protection. These domestic rituals show how the deity’s presence moves beyond monastic walls. At the same time, teachers caution that protector practice should be paired with ethical behavior. Without this, the household recitations lose their grounding.

The surviving sources for Six-Arm Mahākāla are extensive but uneven. Some early manuals have disappeared, while others survive only through later compilations. This is typical for protector practices, which often develop through ritual lineage rather than single authoritative scriptures. Because of this, scholars must track recurring phrases and ritual sequences across manuscripts. These repeated elements show how the deity’s form stabilized over time, even when early textual layers remain incomplete.

Across Tibetan ritual texts, Mahākāla is consistently called mgon po (མགོན་པོ་), “the protector,” and drag po (དྲག་པོ་), “the wrathful one.” The Six-Arm form is identified as lcags drug (ལྕགས་དྲུག), literally “six iron.” Invocation sections frequently contain the formula:

Tibetan citation:

བཀའ་སྲུང་ཉམས་ཆགས་སེལ།

Wylie: bka’ srung nyams chags sel

English: “Protector who dispels defilement and decay.”

These phrases signal the deity’s dual role: clearing mental obscurations and stabilizing the practitioner’s environment. Their repetition across regions shows how textual patterns anchored the identity of Mahākāla.

Sakya and Kagyu Root Manuals |

Nyingma Terma Sources |

Gelug Monastic Codes and Cross-References |

|

Sakya and Kagyu are the principal lineages for the Six-Arm form. Their manuals differ, yet share core structures. Sakya texts usually provide a mandala-based setting, while Kagyu materials emphasize direct invocation. Both include four repeating components:

These manuals show that Six-Arm Mahākāla was not a peripheral deity but fully integrated into the ritual calendars of both schools. |

Nyingma terma texts preserve unique visions of Mahākāla. Some emphasize inner protection, presenting the deity as stabilizing subtle meditative states. Others focus on communal protection or environmental balance. A recurring terma line reads: Tibetan citation: This line appears in multiple terma cycles, indicating a wide circulation of the Six-Arm form within Nyingma traditions and reinforcing its legitimacy even when artistic depictions vary. |

Although the Gelug school favors Four-Arm Mahākāla, it still records Six-Arm references in ritual codes. These passages are brief but valuable because they cross-reference the larger protector framework. A common Gelug note reads: Tibetan citation: Even short statements like this show that the Six-Arm form maintained recognized status, though not emphasized. Scholars sometimes use such references to trace how protector practices travel between traditions while keeping distinct priorities. |

Ritual language often preserves continuity better than manuscripts. When a line appears across distant regions, it signals a long-standing ritual inheritance.

A widely shared chant is:

Tibetan citation:

གདོན་སྲིད་ཀུན་སེལ་མགོན་པོ་དགའ་ལྡན།

Wylie: gdon srid kun sel mgon po dga’ ldan

English: “Protector who removes all disturbances and harmful forces.”

This line survives in Amdo, Kham, and Central Tibet, even when the ritual contexts differ. It allows researchers to detect underlying unity beneath regional style.

Students often ask whether there is a single root scripture for Six-Arm Mahākāla. Tibetan teachers answer cautiously. Protector traditions typically arise from layered transmissions rather than from one canonical source. Although some manuals appear earlier, none can claim exclusivity.

One often-quoted Tibetan reminder is:

This line captures the balance between diversity and continuity. Researchers must learn to work with incomplete histories without forcing artificial origins.

In the modern world, Six-Arm Mahākāla has taken on roles that extend beyond traditional protector duties. Tibetan communities in exile look to him for cultural stability, while Western practitioners encounter him primarily through meditation centers and ritual workshops. These new settings reshape the meaning of protection. Instead of guarding monastic boundaries, Mahākāla often protects psychological resilience, community identity, or spiritual continuity in unfamiliar environments. Tibetan teachers acknowledge this shift. They warn against diluting the tradition, yet they recognize that protector practice is naturally adaptive.

Many contemporary practitioners describe Mahākāla less as a ritual agent and more as a stabilizer of emotional life. They draw on his imagery to confront anxiety, trauma, or inner conflict. Tibetan teachers sometimes emphasize that wrathful deities work well within the mind’s shadowed areas. The deity’s dark body represents a space that can absorb distress without collapsing. The fire symbolizes the energy needed to reclaim clarity. Although traditional texts do not frame Mahākāla in psychological terms, this interpretation resonates with modern needs.

In contemporary communities, Mahākāla is often invoked to establish emotional or ethical boundaries. Practitioners say his imagery helps them recognize when they must say no, withdraw from harmful situations, or protect their practice time. This is not an ancient interpretation, but it aligns with traditional themes. Tibetan texts frequently describe Mahākāla as clearing the path so that clarity and discipline can mature. Modern practitioners simply translate this into psychological terms.

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY