This article examines the mantra Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā within the historical, doctrinal, ritual, and cultural frameworks of Tibetan Buddhism. The study situates it the lived religious ecosystem of Indo-Tibetan Vajrayāna. By tracing the historical emergence of Tārā from Indian Mahāyāna contexts to her full integration into Tibetan Buddhist ritual life, the article clarifies the function of the Tārā mantra as a practice of swift, responsive compassion.

The analysis addresses five core dimensions: historical formation, doctrinal identity, ritual application, comparative function in relation to Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ, and the role of the mantra in Tibetan daily life and its global transmission. Drawing on canonical texts, tantric literature, and ethnographic scholarship, the article argues that the Tārā mantra represents a distinct mode of Buddhist practice centered on immediacy, protection, and actionable liberation. The study aims to bridge academic analysis and practical understanding, providing a framework accessible to scholars, practitioners, and informed readers alike.

This study adopts an interdisciplinary approach combining textual analysis, historical contextualization, and ritual studies. It does not aim to provide a complete philological reconstruction of Tārā-related sources, but rather to clarify how the mantra functions within Tibetan Buddhism as both doctrine and lived practice. Tibetan and Sanskrit technical terms are retained where necessary and explained in a scholarly glossary.

Tārā is one of the most beloved figures in Tibetan Buddhism, known for her swift protection and compassionate response to danger and fear. Her mantra, Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā, is recited daily by monks, nuns, and lay practitioners alike.

Tārā did not originate within Tibetan Buddhism. Her formation belongs to the late Indian Mahāyāna and early Vajrayāna period, roughly between the sixth and eighth centuries CE. This period marks a structural shift in Buddhist ritual culture, characterized by three converging developments:

Within this milieu, Tārā did not arise as an autonomous deity. Early Sanskrit sources situate her within the Avalokiteśvara cultic complex. She is described as an emanation born from Avalokiteśvara’s compassion upon encountering the suffering of beings. The well-known narrative of Tārā arising from Avalokiteśvara’s tears encodes a doctrinal reorientation: compassion ceases to function solely as contemplative intent and becomes immediate liberative activity.

Tibetan sources preserve this relationship unambiguously. Tārā is consistently identified as an emanation (sprul pa) of Avalokiteśvara:

སྒྲོལ་མ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ཀྱི་སྤྲུལ་པ་ཡིན།

Drolma is an emanation of Avalokiteśvara.

By the seventh century, Tārā became the central focus of distinct tantric materials later classified as Tārā Tantras. These texts emphasize protection, rapid intervention, and liberation from concrete dangers, including fear, disease, and hostile forces. Their orientation is pragmatic rather than speculative. Tārā’s efficacy lies in responsiveness rather than metaphysical abstraction.

A defining feature of early Tārā practice is accessibility. Unlike many tantric systems requiring elite initiation contexts, Tārā rituals circulated across monastic institutions, royal courts, and popular religious environments. This openness facilitated her transmission to Tibet during the period of early dissemination (snga dar, seventh–ninth centuries).

Tibetan historical narratives associate Tārā closely with royal patronage. Queen Wencheng and Queen Bhrikuti were retrospectively identified as manifestations of Tārā. While hagiographical, these identifications signal Tārā’s strategic role in embedding Buddhist ritual within Tibetan political and cultural structures. Tārā functioned as a stabilizing ritual presence during a formative period of state-sponsored Buddhism.

By the eleventh century, during the later dissemination (phyi dar), Tārā was fully integrated into the ritual systems of all major Tibetan Buddhist schools. Liturgical texts such as the Praise to the Twenty-One Tārās became standardized. Mantra recitation replaced complex ritual elaboration as the primary mode of engagement. At this stage, Tārā no longer functioned merely as a protective figure but as a paradigm of liberative activity suited to conditions of uncertainty and urgency.

Tārā’s rise did not displace Avalokiteśvara. It clarified a functional distinction within the economy of compassion. Avalokiteśvara embodies compassion as continuous presence. Tārā embodies compassion as immediate response. Tibetan sources articulate this distinction implicitly through usage rather than theory, a distinction later essential for understanding why the Tārā mantra occupies a role distinct from, yet complementary to, Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ.

In Tibetan Buddhism, a mantra is inseparable from its owner (bdag po). To ask what Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā means without first establishing whose mantra it is constitutes a categorical error. The Tārā mantra belongs to Tārā as a fully realized bodhisattva operating within the Vajrayāna framework, not as a symbolic abstraction or auxiliary deity.

Tārā is consistently positioned within Tibetan doctrinal systems as an emanational figure (sprul pa) of Avalokiteśvara (Chenrezig). This relationship is not hierarchical but functional. Avalokiteśvara embodies compassion as uninterrupted presence. Tārā embodies compassion as mobilized response.

This distinction is preserved across textual, ritual, and iconographic sources. Tibetan exegetical traditions do not debate whether Tārā is separate from Avalokiteśvara; they clarify how her mode of activity differs.

Tārā’s identity is further clarified through her name. The Tibetan Drolma derives from the Sanskrit Tārā, “she who liberates.” Liberation here is not abstract emancipation but concrete crossing—rescue from fear, danger, and obstruction. The semantic field of tar (“to cross over”) situates Tārā within a soteriology of movement rather than attainment.

This functional orientation explains why Tārā practices are frequently invoked in situations requiring immediacy: travel, illness, childbirth, political instability, and personal crisis. Her mantra is not primarily contemplative. It is operative.

The multiplicity of Tārā forms is systematized in the well-known liturgical cycle of the Twenty-One Tārās. This cycle does not represent twenty-one separate deities but twenty-one modalities of enlightened activity. Each Tārā corresponds to a specific configuration of obstacle and response.

Structurally, the Twenty-One Tārās function as:

Tibetan liturgical texts emphasize that reciting the Praise to the Twenty-One Tārās is sufficient practice in itself. No complex visualization is required at the basic level.

Tārā’s doctrinal position explains why her mantra differs fundamentally from Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ. While the latter articulates the cultivation of universal compassion and the purification of the six realms, the Tārā mantra functions as an instrument of intervention. It does not replace Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ. It presupposes it.

Within Tibetan practice, these mantras occupy complementary roles. Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ stabilizes compassion as an enduring orientation. Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā mobilizes compassion under pressure.

The mantra Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā functions in Tibetan Buddhism as an applied ritual formula rather than a contemplative slogan. Its primary purpose is not doctrinal exposition but operational intervention. The mantra is invoked to interrupt concrete forms of danger, fear, and obstruction. Its efficacy is framed in terms of response, not attainment.

This orientation is consistent across tantric manuals, liturgical praises, and oral instructions. The mantra is treated as sufficient practice when circumstances demand immediacy. It does not require philosophical elaboration to be effective.

Traditional explanations distinguish three layers of function embedded in the mantra’s structure:

These layers are not sequential stages of meditation. They correspond to degrees of intervention. The mantra escalates response according to the intensity of the situation.

Tibetan ritual texts consistently describe the mantra’s application in situations where delay itself becomes harmful. Commonly cited contexts include:

In these contexts, Tārā practice is not framed as a long-term soteriological project. It is framed as immediate care.

Ritual instructions emphasize simplicity. At the foundational level, no empowerment is required to recite the mantra. Visualization is minimal or optional. What is required is intentional clarity. Tibetan manuals repeatedly state that sincerity (mos gus) and focused recitation suffice.

མོས་གུས་དང་སྒྲ་གཅིག་གིས་གྲོལ།

Liberation is effected through devotion and a single sound.

Giải thoát được thực hiện bằng lòng chí thành và một âm thanh.

This instruction reflects a broader Vajrayāna principle: when circumstances are urgent, practice must be executable without elaborate preparation.

In daily practice, the mantra is commonly integrated in three formats:

These formats are not ranked hierarchically. Appropriateness is determined by context, not ritual completeness.

The mantra’s practical orientation explains why it does not compete with Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ. The latter cultivates compassion as a stable disposition. The Tārā mantra activates compassion when stability is compromised. One sustains the path. The other intervenes when the path is threatened.

If Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ already articulates universal compassion, then the emergence of Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā demands explanation. Tibetan ritual usage provides it. The Mani mantra stabilizes the practitioner’s orientation over time. It assumes continuity, repetition, and gradual cultivation. The Tārā mantra assumes none of these.

Tārā practices appear most prominently in situations where cultivation cannot proceed normally:

In these contexts, practice cannot wait to mature. Compassion must act before it reflects.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the Tārā mantra is embedded within ritual structures that privilege usability over complexity. Its practice is intentionally scalable. It functions across a spectrum ranging from full tantric sādhanā to minimal recitation in everyday contexts. This adaptability explains its longevity and cultural saturation.

At the formal level, the mantra appears within short and long Tārā sādhanas transmitted across all major Tibetan schools. These rituals share a stable core:

The emphasis lies on continuity rather than ritual elaboration. Even in monastic settings, Tārā practices are among the shortest regularly performed sādhanas.

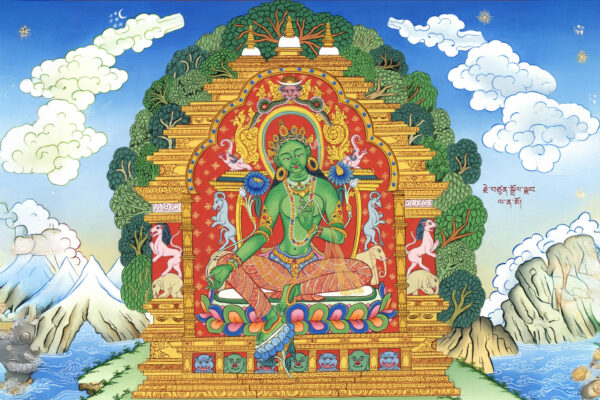

Visualization instructions are deliberately minimal at the foundational level. Practitioners are instructed to visualize Tārā either in front or above the crown, green in color, embodying alert compassion. No complex mandala construction is required. Gesture (mudrā) and ritual implements are optional.

This minimalism is doctrinally justified. Tibetan manuals emphasize that excessive ritualization can obstruct responsiveness. The mantra must remain executable under pressure.

གནས་སྐབས་དུས་ལ་སྒྲུབ་པ་སླ་བ་དགོས།

Practice must be easy to perform in moments of urgency.

Beyond formal ritual, the Tārā mantra occupies a central place in Tibetan daily life. It is recited by lay practitioners, particularly women, in contexts of caregiving, travel, illness, and childbirth. Unlike more contemplative practices, Tārā recitation integrates seamlessly with ordinary activity.

Ethnographic accounts consistently note that Tārā functions as a domestic presence. Her mantra is spoken while walking, working, or caring for others. This integration dissolves the boundary between ritual space and lived space.

Culturally, Tārā’s prominence also reflects gendered dimensions of Tibetan religiosity. While doctrinally transcending gender, Tārā provides a symbolic and practical locus for female religious agency. This dimension contributed to her enduring popularity and facilitated her transnational transmission in the twentieth century.

As Tibetan Buddhism spread globally, Tārā practices became among the first tantric forms taught to non-Tibetan audiences. Their relative simplicity, ethical clarity, and lack of exclusivity made them accessible without significant cultural translation. The mantra’s international circulation did not diminish its ritual integrity.

The centrality of Tārā in Tibetan daily life confirms this functional reading. Her mantra is recited not primarily in formal ritual halls, but in kitchens, on roads, during labor, illness, and care. Ethnographic accounts repeatedly note that Tārā is invoked while moving, working, and tending to others.

This domestic embeddedness is not incidental. It reflects a conception of practice that refuses to wait for ideal conditions. Tārā’s prominence among women practitioners further underscores this orientation: care, risk, and immediacy are not abstract themes but lived realities.

This study has examined Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā as a living component of Tibetan Buddhism rather than a marginal devotional formula. Across historical, doctrinal, ritual, and cultural dimensions, the Tārā mantra emerges as a practice designed for immediacy. Its defining feature is not metaphysical complexity but functional clarity.

Historically, Tārā arose within late Indian Mahāyāna and early Vajrayāna contexts as an emanational expression of Avalokiteśvara’s compassion. Her transmission to Tibet coincided with periods of political formation and social uncertainty, conditions under which practices emphasizing protection and rapid response gained particular relevance. This historical trajectory explains both her early royal patronage and her subsequent popular diffusion.

Doctrinally, the Tārā mantra articulates a distinct modality of compassion. Whereas Oṃ Maṇi Padme Hūṃ cultivates compassion as a stable and universal orientation, Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā mobilizes compassion as intervention. The two mantras operate within a shared ethical horizon while fulfilling different functions within Tibetan practice.

Ritually, the mantra’s strength lies in its scalability. It functions within full tantric sādhanas, abbreviated liturgies, and minimal daily recitation without loss of coherence. This flexibility is not a concession to modernity but a feature already present in Tibetan ritual manuals. The practice is structured to remain executable under conditions of urgency.

Culturally, the Tārā mantra has shaped Tibetan religious life at the domestic level. Its association with caregiving, travel, illness, and childbirth embedded it within everyday experience, particularly among women. This integration enabled its smooth transmission beyond Tibet in the twentieth century, where it became one of the most widely practiced Vajrayāna mantras internationally.

Taken together, these dimensions clarify why the Tārā mantra has neither displaced nor been displaced by other central practices. It persists because it addresses a specific need within the Buddhist path: the need for a form of practice that responds when stability is compromised. In this sense, Oṃ Tāre Tuttāre Ture Svāhā functions as a ritual articulation of compassion under pressure.

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY

GIAO LONG MONASTERY